OSG helps LIGO scientists confirm Einstein's unproven theory

February 11, 2016

Albert Einstein first posed the idea of gravitational waves in his general theory of relativity just over a century ago. But until now, they had never been observed directly. For the first time, scientists with the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) Scientific Collaboration (LSC) have observed ripples in the fabric of spacetime called gravitational waves.

LIGO consists of two observatories within the United States—one in Hanford, Washington and the other in Livingston, Louisiana—separated by 1,865 miles. LIGO’s detectors search for gravitational waves from deep space. With two detectors, researchers can use differences in the wave’s arrival times to constrain the source location in the sky. LIGO’s first data run of its advanced gravitational wave detectors began in September 2015 and ran through January 12, 2016. The first gravitational waves were detected on September 14, 2015 by both detectors.

The LIGO project employs many concepts that the OSG promotes—resource sharing, aggregating opportunistic use across a variety of resources—and adds two twists: First, this experiment ran across LIGO Data Grid (LDG), OSPool and Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE)-based resources, all managed from a single HTCondor-based system to take advantage of dedicated LDG, opportunistic OSG and NSF eXtreme Digital (XD) allocations. Second, workflows analyzing LIGO detector data proved more data-intensive than many opportunistic OSG workflows. Despite these challenges, LIGO scientists were able to manage workflows with the same tools they use to run on dedicated LDG systems—Pegasus and HTCondor.

Peter Couvares, data analysis computing manager for the Advanced LIGO project at Caltech, specializes in distributed computing problems. He and colleagues James Clark (Georgia Tech) and Larne Pekowsky (Syracuse University) explained LIGO’s computing needs and environment: The main focus is on optimization of data analysis codes, where optimization is broadly defined to encompass the overall performance and efficiency of their computing. While they use traditional optimization techniques to make things run faster, they also pursue more efficient resource management, and opportunistic resources—if there are computers available, they try to use them—thus the collaboration with OSG.

“When a workflow might consist of 600,000 jobs, we don’t want to rerun them if we make a mistake. So we use DAGMan (Directed Acyclic Graph Manager, a meta-scheduler for HTCondor) and Pegasus workflow manager to optimize changes,” added Couvares. “The combination of Pegasus, Condor, and OSG work great together.” Keeping track of what has run and how the workflow progresses, Pegasus translates the abstract layer of what needs to be done into actual jobs for Condor, which then puts them out on OSG.

The computing model

Since this work encompasses four types of computing – volunteer, dedicated, opportunistic (OSG), and allocated (XSEDE XD via OSG) – everything needs to be very efficient. Couvares helps with coordination, Pekowsky with optimization, and Clark with using OSG. In particular, OSG also enabled access to allocation-based resources from XSEDE. Allocations allow LIGO to get fixed amounts of time on dedicated NSF-funded supercomputers Comet and Stampede. While Stampede looks and behaves very much like a traditional supercomputer resource (batch, login node, shared file system), Comet has a new virtualization-based interface that eliminates the need to submit to a batch system. OSG provides this through a virtual machine (VM) image, then LIGO simply uses the OSG environment.

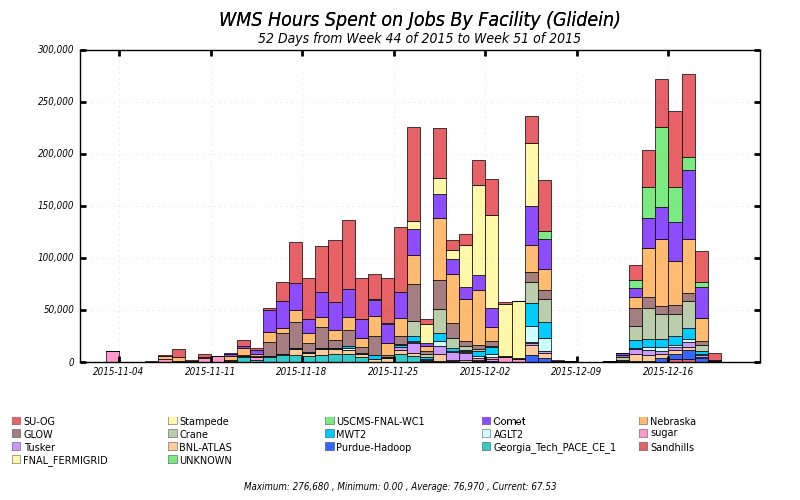

LIGO consumed 3,956,910 hours on OSG, out of which 628,602 hours were on the Comet and 430,960 on the Stampede XD resources. OSG’s Brian Bockelman (University of Nebraska-Lincoln) and Edgar Fajardo (UC San Diego/San Diego Supercomputer Center) used HTCondor to help LIGO implement their Pegasus workflow transparently across 16 clusters at universities and national labs across the US, including on the NSF-funded Comet and Stampede supercomputers.

“Normally our computing is done on dedicated clusters on the LIGO Data Grid,” said Couvares, “but we are moving toward also using outside and more elastic resources like OSG. OSG allows more flexibility as we add in systems that aren’t part of our traditional dedicated systems. The combination of OSG for unusual or dynamic workloads, and the LIGO Data Grid for regular workloads keeping up with new observational data is very powerful. In addition, Berkely Open Infrastructure for Network Computer (BOINC) allows us to use volunteers’ home computers when they are idle, running Pulsar searches around the world in the Einstein@Home project (E@H). The aggregated cycles from E@H are quite large but it is well-suited to only some kinds of searches where a computer must process a smaller amount of data for a longer amount of time.” We must rely on traditional HTC resources for our data-intensive analysis codes.

LIGO codes cannot all run as-is on OSG. The majority of codes are highly optimized for the LDG environment, so they identified the most compute-intensive and high science priority code to run on OSG. Of about 100 different data analysis codes, only a small handful are running on OSG so far. However, the research team started with the hardest code, their highest priority, which means they are now doing some of LIGO’s most important computing on OSG. Other low latency codes must run on dedicated local resources where they might need to be done in seconds or minutes.

“It is important that LIGO has a broad set of resources and an increasingly diverse set of resources. OSG is almost like a universal adapter for us,” said Couvares. “It is very powerful, users don’t need to care where a job runs, and it is another step toward that old promise of grid computing.

The importance of OSG and NSF support

Using data analysis run on the OSG, the LIGO team looked for a compact binary coalescence, that is, the merger of binary neutron stars or black holes. Couvares called it a modeled search—they have a signal that they believe is a strong indicator, they know what it’s going to look like, and they have optimal match filters to compare data with the signal they expect. But the search is computationally expensive because it’s not just one signal they are looking for: The parameters of the source may change or the objects may spin differently. The degree of match requires a search on the order of 100,000 different models/waveforms. This makes the OSG very valuable, because it can split up many of the match filters.

“The parallel nature of the OSG is what’s valuable,” said Couvares. “It is well suited to a high throughput environment. We would like to use more OSG resources because we could expand the parameter space of our searches beyond what is possible with dedicated resources. We need two things, really. We obviously need resources, but we also need people who can be a bridge between the data analysts/scientists and the computing resources. Resources alone are not enough. LIGO will always need dedicated in-house computing for low latency searches that need to be done quickly, and for our steady-state offline computing, but now we have the potential elasticity of OSG.”

“The nature of our collaboration with OSG has been absolutely great for a number of reasons,” said Couvares. “The OSG people have been extremely helpful. They are really unselfish and technical. That’s not always there in the open-source world. The basic idea of OSG has been good for LIGO—their willingness OSG services for LIGO, to reduce the barrier to entry, setting up computing elements, and so on. The barrier otherwise would have been too high. We couldn’t be happier with our partnership.”

Another big step has been the increase in network speed. The data was cached at the University of Nebraska and streamed to on-demand worker nodes that are able to read from a common location. This project benefited greatly from the NSF’s Campus Cyberinfrastructure – Network Infrastructure and Engineering (CC-NIE) program, which helped provide a hardware upgrade from 10Gbps to 100Gbps WAN connectivity. Receiving NSF support to upgrade to 100Gbps has enabled huge gains in workflow throughput.

The LIGO analysis ran across 16 different OSG resources, for a total of 4M CPU hours:

- 1M CPU hour (25%) XSEDE contribution<

- 5 TB total input data, cached at the Holland Computing Center (HCC) at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln

- 1 PB total data volume distributed to jobs from Nebraska

- 10 Gbps sustained data rates from Nebraska storage to worker nodes

Couvares concluded, “What we are doing is pure science. We are trying to understand the universe, trying to do what people have wanted to do for 100 years. We are extending the reach of human understanding. It’s very exciting and the science is that much easier with the OSG.”

– Greg Moore

– Brian Bockelman (OSG, University of Nebraska at Lincoln) contributed to this story