OSG User School 2022 Researchers Present Inspirational Lightning Talks

By: Hannah Cheren

December 19, 2022

The OSG User School student lightning talks showcased their research, inspiring all the event participants.

Each summer, the OSG Consortium offers a week-long summer school for researchers who want to learn how to use high-throughput computing (HTC) methods and services to handle large-scale computing applications at the heart of today’s cutting-edge science. This past summer the school was back in-person on the University of Wisconsin–Madison campus, attended by 57 students and over a dozen staff.

Participants from Mali and Uganda, Africa, to campuses across the United States learned through lectures, discussions, and hands-on activities how to apply HTC approaches to handle large ensembles of jobs and large datasets in support of their research work. “It’s truly humbling to see how much cool work is being done with computing on @CHTC_UW and @opensciencegrid!!” research facilitator Christina Koch tweeted regarding the School.

One highlight of the School is the closing participants’ lightning talks, where the researchers present their work and plans to integrate HTC, expanding the scope and goals of their research. The lightning talks given at this year’s OSG User School illustrate the diversity of students’ research and its expanding scope enabled by the power of HTC and the School.

Note: Applications to attend the School typically open in March. Check the OSG website for this announcement.

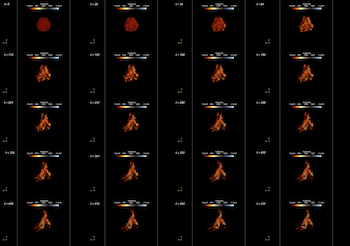

Devin Bayly, a data and visualization consultant at the University of Arizona’s Research Technologies department, presented “OSG for Vulkan StarForge Renders.” Devin has been working on a multimedia project called Stellarscape, which combines astronomy data with the fine arts. The project aims to pair the human’s journey with a star’s journey from birth to death.

His goal has been to find a way to support connections with the fine arts, a rarity in the HTC community. After attending the User School, Devin intends to use the techniques he learned to break up his data and entire simulation into tiles and use a low-level graphics API called Vulkan to target and render the data on CPU/GPU capacity. He then intends to combine the tiles into individual frames and assemble them into a video.

simulation gas position data.

Starforge Anvil of Creation: Grudi’c, Michael Y. et al. “STARFORGE: Toward a comprehensive numerical model of star cluster formation and feedback.” arXiv: Instrumentation and Methods for Astrophysics (2020): n. pag. https://arxiv.org/abs/2010.11254

Mike Nsubuga, a Bioinformatics Research fellow at the African Center of Excellence in Bioinformatics and Data-Intensive Sciences (ACE) within the Infectious Disease Institute (IDI) at Makerere University in Uganda, presented “End-to-End AI data systems for targeted surveillance and management of COVID-19 and future pandemics affecting Uganda.”

Nsubuga noted that in the United States, there are two physicians for every 1000 people; in Uganda, there is only one physician per 25,000 people. Research shows that AI, automation, and data science can support overburdened health systems and health workers when deployed responsibly. Nsubuga and a team of Researchers at ACE are working on creating AI chatbots for automated and personalized symptom assessments in English and Luganda, one of the major languages of Uganda. He’s training the AI models using data from the public and healthcare workers to communicate with COVID-19 patients and the general public.

While at the School, Nsubuga learned how to containerize his data into a Docker image, and from that, he built an Apptainer (formerly Singularity) container image. He then deployed this to the Open Science Pool (OSPool) to determine how to mimic the traditional conversation assistant workflow model in the context of COVID-19. The capacity offered by the OSPool significantly reduced the time it takes to train the AI model by eight times.

Jem Guhit, a Physics Ph.D. candidate from the University of Michigan, presented “Search for Di-Higgs production in the LHC with the ATLAS Experiment in the bbtautau Final State.” The Higgs boson was discovered in 2012 and is known for the Electroweak Symmetry Breaking (EWSB) phenomenon, which explains how other particles get mass. Since then, the focus of the LHC has been to investigate the properties of the Higgs boson, and one can get more insight into how the EWSB Mechanism works by searching for two Higgs bosons using the ATLAS Detector. The particle detectors capture the resultant particles from proton-proton collisions and use this as data to look for two Higgs bosons.

DiHiggs searches pose a challenge because the rate at which a particle process occurs for two Higgs bosons is 30x smaller than for a single Higgs boson. Furthermore, the particles the Higgs can decay to have similar particle trajectories to other particles produced in the collisions unrelated to the Higgs boson. Her strategy is to use a machine learning (ML) method powerful enough to handle complex patterns to determine whether the decay products come from a Higgs boson. She plans to use what she’s learned at the User School to show improvements in her machine-learning techniques and optimizations. With these new skills, she has been running jobs on the University of Michigan’s HTCondor system utilizing GPU and CPUs to run ML jobs efficiently and plans to use the OSPool computing cluster to run complex jobs.

Peder Engelstad, a spatial ecologist and research associate in the Natural Resource Ecology Laboratory at Colorado State University (and 2006 University of Wisconsin-Madison alumni), presented a talk on “Spatial Ecology & Invasive Species.” Engelstad’s work focuses on the ecological importance of natural spatial patterns of invasive species.

He uses modeling and mapping techniques to explore the spatial distribution of suitable habitats for invasive species. The models he uses combine locations of species with remotely-sensed data, using ML and spatial libraries in R. Recently. he’s taken on the massive task of creating thousands of suitability maps. To do this sequentially would take over three years, but he anticipates HTC methods can help drastically reduce this timeframe to a matter of days.

Engelstad said it’s been exciting to see the approaches he can use to tackle this problem using what he’s learned about HTC, including determining how to structure his data and break it into smaller chunks. He notes that the nice thing about using geospatial data is that they are often in a 2-D grid system, making it easy to index them spatially and designate georeferenced tiles to work on. Engelstad says that an additional benefit of incorporating HTC methods will be to free up time to work on other scientific questions.

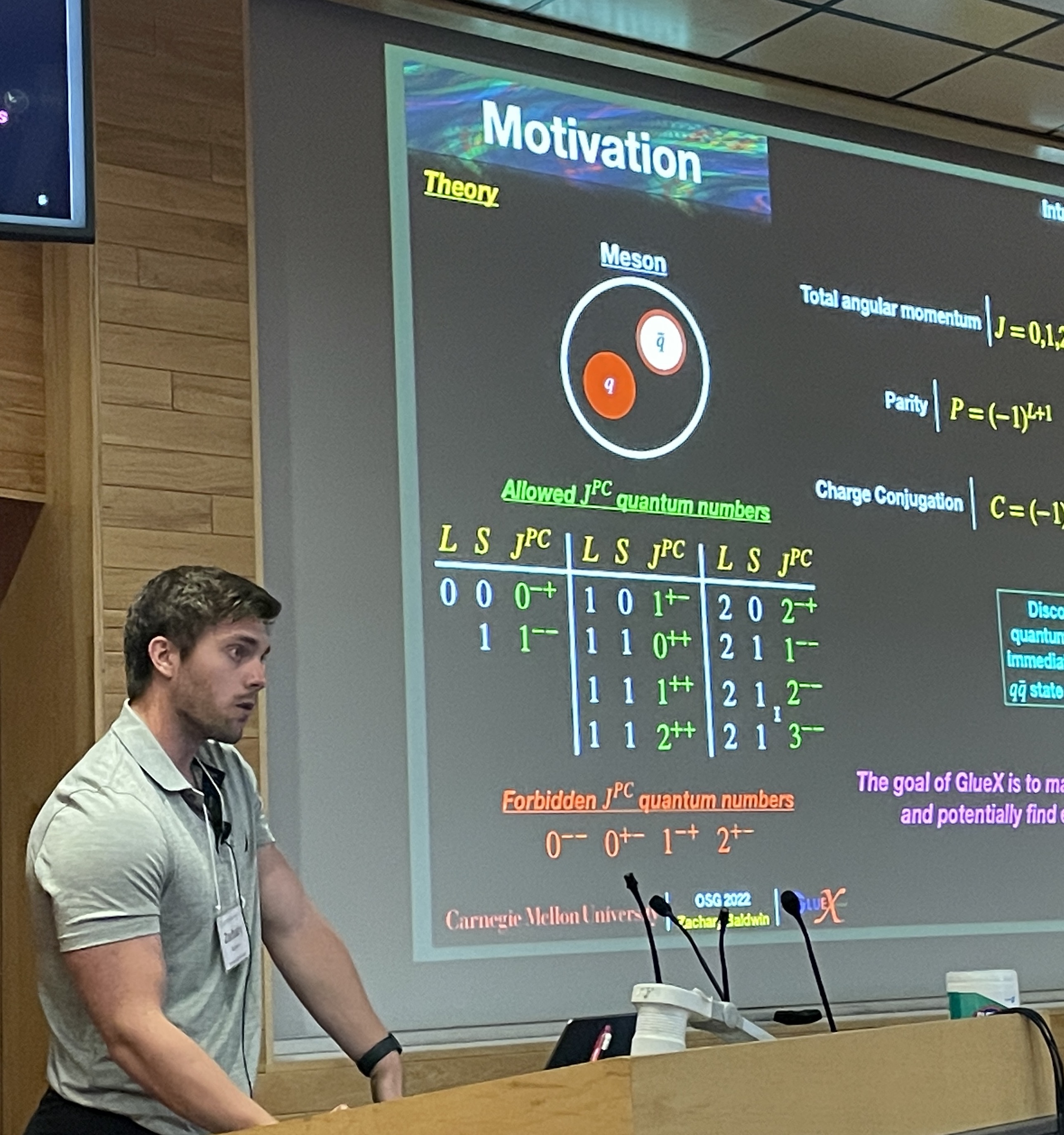

Zachary Baldwin, a Ph.D. candidate in Nuclear and Particle Physics at Carnegie Mellon University, works for the GlueX Collaboration, a particle physics experiment at the Thomas Jefferson National Lab that searches for and studies exotic hybrid mesons. Baldwin presented a talk on “Analyzing hadronic systems in the search for exotic hybrid mesons at GlueX.”

His thesis looks at data collected from the GlueX experiment to possibly discover forbidden quantum numbers found within subatomic particle systems to determine if they exist within our universe. Baldwin’s experiment takes a beam of electrons, speeds them up to high energies, and then collides them with a thin diamond wafer. These electrons then slow down, producing linearly polarized photons. These photons will then collide with a container of liquid hydrogen (protons) within the center of his experiment. Baldwin studies the resulting systems produced within these photon-proton collisions.

The collision creates billions of particles, leaving Baldwin with many petabytes of data. Baldwin remarks that too much time gets wasted looping through all the data points, and massive processes run out of memory before he can compute results, which is one aspect where HTC comes into play. Through the User School, another major area he’s been working on is simulating Monte Carlo particle reactions using OSPool’s containers which he pushes into the OSPool using HTCondor to simulate events that he believes would happen in the real world.

Olaitan Awe, a systems analyst in the Information Technology department at the Jackson Laboratory (JAX), presented “Newborn Screening (NBS) of Inborn Errors of Metabolism (IEM).” The goal of newborn screening is that, when a baby is born, it detects early what diseases they might have.

Genomic Newborn Screenings (gNBS) are generally cheap, detect many diseases, and have a quick turnaround time. The gNBS takes a child’s genome and compares it to a reference genome to check for variations. The computing challenge lies in looking for all variations, determining which are pathogenic, and seeing which diseases they align with.

After attending the User School, Awe intends to tackle this problem by writing DAGMan scripts to implement parent-child relations in a pipeline he created. He then plans to build custom containers to run the pipeline on the OSPool and stage big data shared across parent-child processes. The long-term goal is to develop a validated, reproducible gNBS pipeline for routine clinical practice and apply it to African populations.

Max Bareiss, a Ph.D. Candidate at the Virginia Tech Center for Injury Biomechanics presented “Detection of Camera Movement in Virginia Traffic Camera Video on OSG.” Bareiss used a data set of 1263 traffic cameras in Virginia for his project. His goal was to determine how to document the crash, near-crashes, and normal driving recorded by traffic cameras using his video analysis pipeline. This work would ultimately allow him to detect vehicles and pedestrians and determine their trajectories.

The three areas he wanted to tackle and obtain help with at the User School were data movement, code movement, and using GPUs for other tasks. For data movement, he used MinIO, a high-performance object storage, so that the execution points could directly copy the videos from Virginia Tech. For code movement, Bareiss used Alpine Linux and multi-stage build, which he learned to implement throughout the week. He learned about using GPUs at the Center for High Throughput Computing (CHTC) and in the OSPool.

Additionally, he learned about DAGMan, which he noted was “very exciting” since his pipeline was already a directed acyclic graph (DAG).

Matthew Dorsey, a Ph.D. candidate in the Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering Department at North Carolina State University, presented on “Computational Studies of the Structural Properties of Dipolar Square Colloids.”

Dorsey is studying a colloidal particle developed in a research lab at NC State University in the Biomolecular Engineering Department. His research focuses on using computer models to discover what these particles can do. The computer models he has developed explore how different parameters (like the system’s temperature, particle density, and the strength of an applied external field) affect the particle’s self-assembly.

Dorsey recently discovered how the magnetic dipoles embedded in the squares lead to structures with different material properties. He intends to use the HTCondor Software Suite (HTCSS) to investigate the applied external fields that change with respect to time. “The HTCondor system allows me to rapidly investigate how different combinations of many different parameters affect the colloids’ self-assembly,” Dorsey says.

Ananya Bandopadhyay, a graduate student from the Physics Department at Syracuse University, presented “Using HTCondor to Study Gravitational Waves from Binary Neutron Star Mergers.”

Gravitational waves are created when black holes or neutron stars crash into each other. Analyzing these waves helps us to learn about the objects that created them and their properties.

Bandopadhyay’s project focuses on LIGO’s ability to detect gravitational wave signals coming from binary neutron star mergers involving sub-solar mass component stars, which she determines from a graph which shows the detectability of the signals as a function of the component masses comprising the binary system.

The fitting factors for the signals would have initially taken her laptop a little less than a year to run. She learned how to use OSPool capacity from the School, where it takes her jobs only 2-3 days to run. Other lessons that Bandopadhyay hopes to apply are data organization and management as she scales up the number of jobs. Additionally, she intends to implement containers to help collaborate with and build upon the work of researchers in related areas.

Meng Luo, a Ph.D. student from the Department of Forest and Wildlife Ecology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, presented “Harnessing OSG to project the impact of future forest productivity change on land use change.” Luo is interested in learning how forest productivity increases or decreases over time.

Luo built a single forest productivity model using three sets of remote sensing data to predict this productivity, coupling it with a global change analysis model to project possible futures.

Using her computer would take her two years to finish this work. During the User School, Luo learned she could use Apptainer to run her model and multiple events simultaneously. She also learned to use the DAGMan workflow to organize the process better. With all this knowledge, she ran a scenario, which used to take a week to complete but only took a couple of hours with the help of OSPool capacity.

Tinghua Chen from Wichita State University presented a talk on “Applying HTC to Higgs Boson Production Simulations.” Ten years ago, the ATLAS and CMS experiments at CERN announced the discovery of the Higgs boson. CERN is a research center that operates the world’s largest particle physics laboratory. The ATLAS and CMS experiments are general-purpose detectors at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) that both study the Higgs boson.

For his work, Chen uses a Monte Carlo event generator, Herwig 7, to simulate the production of the Higgs boson in vector boson fusion (VBF). He uses the event generator to predict hadronic cross sections, which could be useful for the experimentalist to study the Standard Model Higgs boson. Based on the central limit theorem, the more events Chen can generate, the more accurate the prediction.

Chen can run ten thousand events on his laptop, but the predictions could be more accurate. Ideally, he’d like to run five billion events for more precision. Running all these events would be impossible on his laptop; his solution is to run the event generators using the HTC services provided by the OSG consortium.

Using a workflow he built, he can set up the event generator using parallel integration steps and event generation. He can then use the Herwig 7 event generator to build, integrate, and run the events.

…

Thank you to all the researchers who presented their work in the Student Lightning Talks portion of the OSG User School 2022!